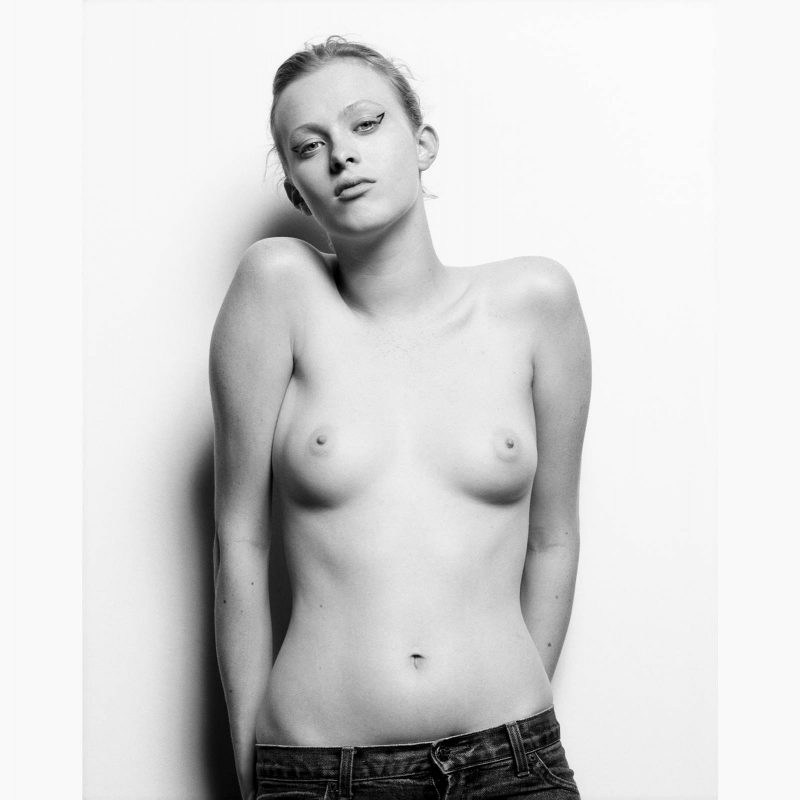

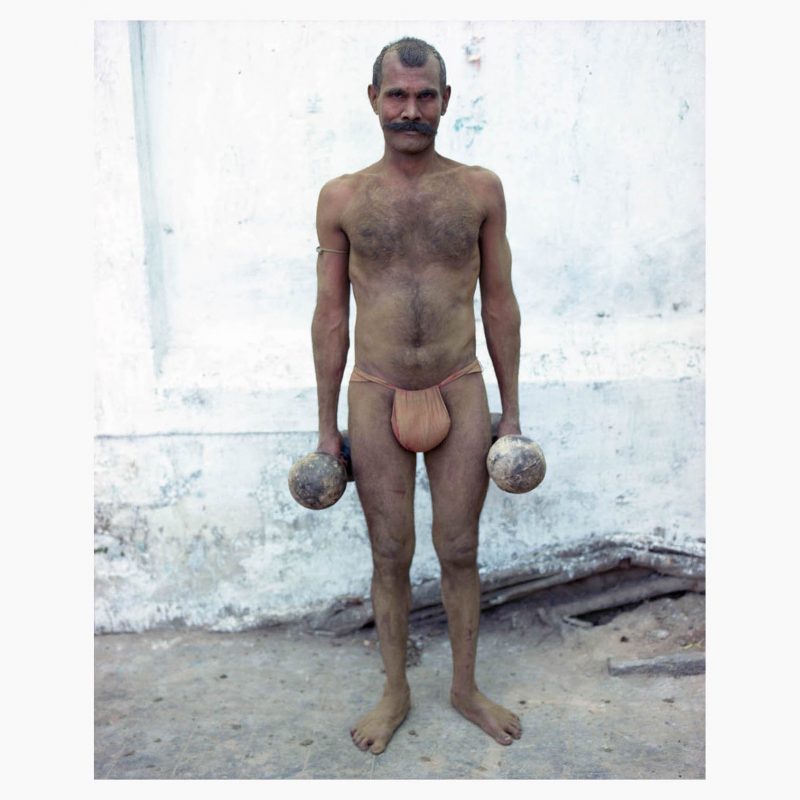

Niels Ackermann on Looking for Lenin.

by Johanna M Lenander & Steen Sundland

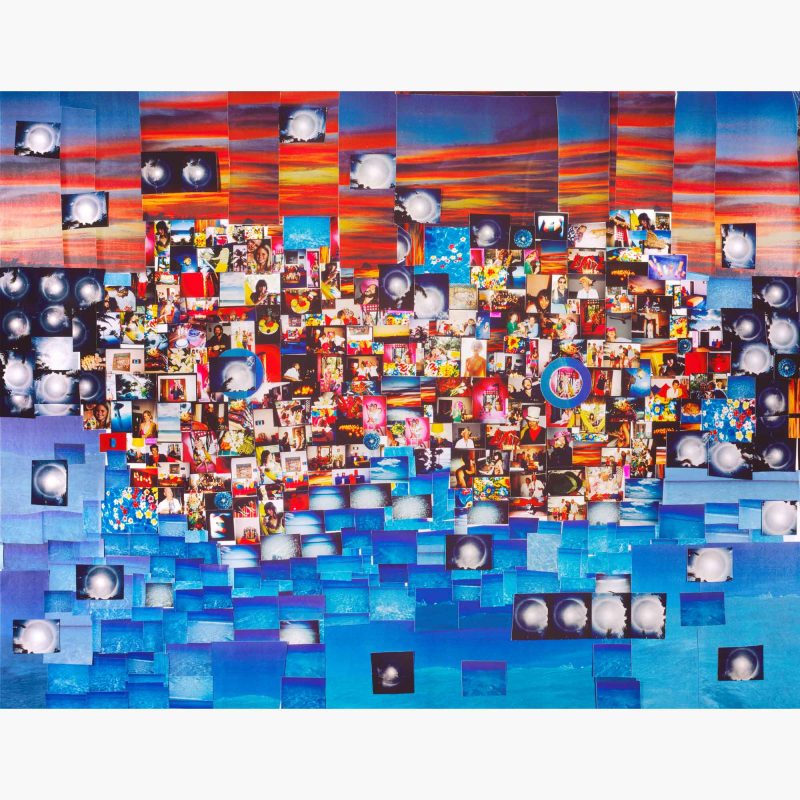

Niels Ackerman takes documentary pictures that show the world from a much greater perspective than his own point of view. Deeply respectful of the cultural, social and political context of the environments he portrays, his aim is to enhance the complexity and contradiction of social experiences, not reduce them to a simplistic storyline. Perhaps that’s why his photos radiate warmth and generosity, as well as a distinct sense of optimism. Because when you manage to represent your subjects with such awareness, love and respect, you have to believe in humanity.

Here, the award-winning photographer, who splits his time between Kiev and Geneva, shares some of the thoughts and positions that fuel his work.

On the beginnings:

I’m first and foremost a geek. I started making websites when I was around 12. And around that age, I also got very interested in graphic design. So I felt I that needed some raw material for my endeavours for which I needed a camera. And since my dad never wanted to lend me his Canon, I started doing little jobs to save money to buy my first digital camera. My inspirations back then were really from graphic arts, mostly painters, especially renaissance paintings touched me a lot. And they taught me about two important visual elements: the sense of composition, how things have to be aligned and placed within the frame, and the importance of light, how you play with the direction of light and how colors interplay.

I came in contact with documentary photography a bit later, when I was 15 and the 2003 G8 Summit was held in a city near Geneva. There were a lot of protests in Geneva that were quite nasty, violent even, as that was the peak of the alternative anti-globalisation movement. So I took my small camera and started documenting these protests and also how the city reacted to them. And I became really fascinated with reportage photography, how to tell real stories with pictures and how you can mix art and journalism, sometimes within one single photo.

After that, I started documenting things for myself, around Switzerland, politics mostly. In 2007, I was signed by Rezo, one of Switzerland’s most successful photo agencies, whose work I had always loved. I was 20 and it was really a dream for me. That was my entry point in media, not just taking pictures for myself, but taking them for newspapers and magazines. I stayed with Rezo until 2015, when some colleagues and I left the agency to created our own, which is called Lundi 13.

On the state of media today:

I started working in this environment in 2007, which was still like some sort of golden years. At least it was for me, the publications I worked with had large budgets. But a year later, there’s the Lehman Brothers crash, and boom, the clients who used to call three times per week, you suddenly don’t hear from for six months. And we had to adapt. I would say that since then, especially during the past two years, the media industry’s decay has been rapidly increasing, not only in financial terms, but also in moral terms. The way it’s evolving—how people digest information, how they behave with facts etc.—means that we constantly have to renegotiate our own position within this environment.

Now, I’m at the point where I’m asking myself: Is it still worth it to work with the media as it is now? I have started to distance myself from it because I’m not getting what I’m looking for in that work anymore. There’s something really disturbing about how we seem to think that media’s role is to oversimplify reality, to make judgments on who’s good and who’s bad. Just think of CNN for example,—although it could really be most of the media outlets—the kind of language and iconography they use to describe the world is extremely stereotypical and simplistic. It’s not bringing more intelligence to people in order for them to understand the world better.

On the role of reportage:

It’s not our role as journalists to call out who is bad and who is good, because in most cases, reality is much more complex than that. You can look at recent history, how the Libyan rebels were initially described as heroes when they were fighting against the Gaddafi regime. Now that they’ve turned into some new terrorist groups, they are depicted as extremely bad. A bit of nuance in the reporting would have avoided having to condemn the same people that you initially praised. The world is not black and white.

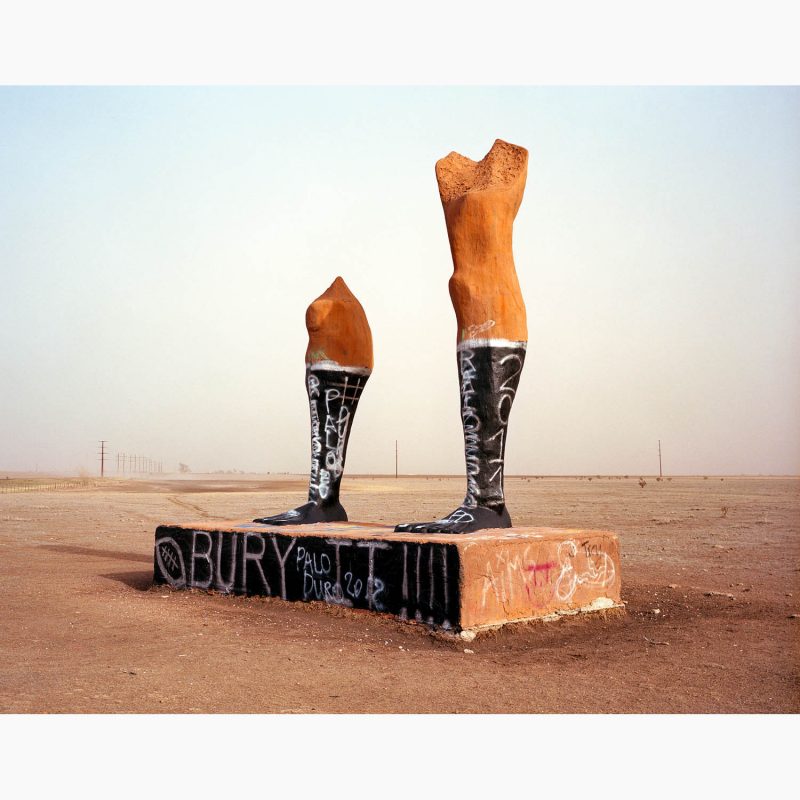

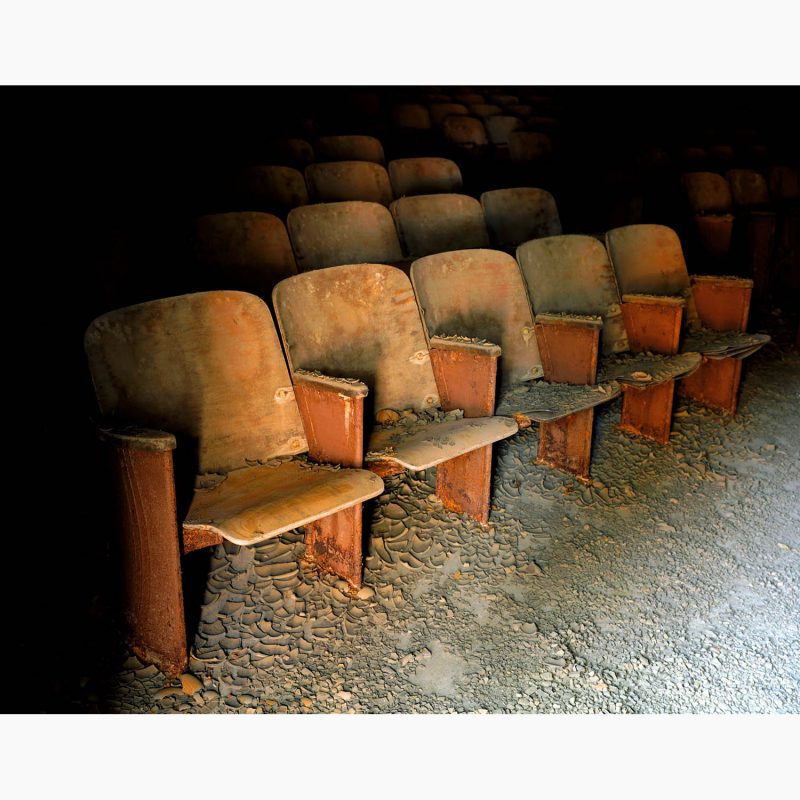

On “Looking for Lenin”:

The “Looking for Lenin” project is really built around this idea of including all points of view on the topic of decommunisation. That’s why the texts that accompany the pictures don’t express our observations or interpretations. Because I think it would be highly inappropriate for us as foreign journalists to start judging and implement our own moral reading. It’s not our country, it’s not our war, it’s not our brothers or sisters or parents who are fighting on the front line or had to escape their house from bombings.

So what Sebastien Gobert, my colleague on this project, and I decided to do was really to stay behind and give a voice to every single

kind of perception. From very nostalgic people who were critical about the destruction of these monuments, to people who reminded us about all the difficulty that came with being part of the Soviet Union, to more philosophical people who said: “Ok, so we’re taking this down now, whatever, but what comes next? What will replace this and what will we do to avoid a new era of totalitarianism?” Bringing all these perspectives together is our small contribution to show how complicated it is to deal with a difficult past. Some people may revere it, some people may condemn it, and it’s possible that both are right.

On cutting through the noise:

Dealing with short attention spans is one of our responsibilities as journalists or visual artists. The world is flooded with information and our stories are just a tiny fraction of the billions of narratives. If my pictures are going to reach people, I have to make sure they grab attention. As a photographer, I think it’s an interesting challenge. You have to take the kind of images that people may have easily skipped over and photographically make them relevant. How you do make a picture that stops people in their tracks to think: “Hey, I’m curious about this thing now”? We have to be a bit like advertising people, we have to create a story that stands out. That’s one issue with war photography nowadays. If you go to a festival like “Visa pour l’Image” in Perpignan, they have amazing works, but they all look more or less the same. How do you make sure that a reader of a magazine can turn the pages and see the difference between this war in Kongo and this war in some South American region or this war in Syria? If the visual language is always the same, people just don’t look at it anymore. For me, that’s a moment when art and journalism connect, when you use a creative element to surprise the viewer. Because if we’re not surprised, we stop looking.

On survival strategies:

It’s true that media budgets are shrinking and publications are getting less and less used to pay for their content. Especially when it’s a personal project. That’s a bit heartbreaking, because when they commission you for portraits to be done quickly in an afternoon, they don’t have any problem paying you. But when you’ve invested five or ten years of your life in a project, the attitude is: “We’re promoting your work, so you have to understand that we won’t pay you anything.” To overcome this, I have developed my own economic system. I call it the “freemium approach”. It’s just like the when you download a free app on your on your phone and have to pay for the extra features.

Basically, I have two sets of images. One is limited to ten pictures that have already been published. I say: “OK, if you have no budget, you’ll get up to eight pic of this initial set , but you have to comply with lots of constraints in terms of size, there can be no paywall and you have to link to my website. However, if you do have a budget, then I can offer you more image selections that your readers won’t be able to see everywhere. So if you want to give your readers added value, you have to pay for it.” This approach works about 60% of the time. And if they won’t pay, but I still have something to gain from the exposure, I will work with them. But if it’s a platform that doesn’t interest me at all, it’s just “no”. This approach is easy to replicate and I never divert from it. It paid for the costs of “Looking for Lenin” and the project I worked on for four years before that. In the end, you can use the best of both worlds.